Fun Facts -- Long Routes.

1) On the ocean.

2) On the land.

3) ... and getting back home again.

2) On the land.

3) ... and getting back home again.

https://www.technologyreview.com/s/611012/computer-scientists-have-found-the-longest-straight-line-you-could-sail-without-hitting/

Computer scientists have found the longest straight line you could sail without hitting land.

While they were at it, they found the longest straight path you could drive without hitting water.

by Emerging Technology from the arXiv

Apr 30, 2018

Back in 2012, a curious debate emerged on the discussion website Reddit, specifically on a subreddit called /r/MapPorn. Here the user Kepleronlyknows posted a map of the world purporting to show the longest navigable straight-line path over water without hitting land. The route began in Pakistan and followed a great circle under Africa and South America until it hit eastern Russia.

The post generated huge debate, with much head-scratching and pawing over charts and globes. The big question was whether the claim was correct—could there be a different straight-line route over water that was longer but uninterrupted by land of any kind? At the same time, same question arose for land—what was the longest straight-line route uninterrupted by lakes or seas?

For cartographers, it is clear that the answers would have to follow a great circle: an arc along one of the many largest imaginary circles that can be drawn around a sphere. Great circles always follow the shortest path between two points on a sphere. But how to find the great circles that contain the solutions?

The longest straight-line land journey on Earth.

Computer scientists have found the longest straight line you could sail without hitting land.

While they were at it, they found the longest straight path you could drive without hitting water.

by Emerging Technology from the arXiv

Apr 30, 2018

Back in 2012, a curious debate emerged on the discussion website Reddit, specifically on a subreddit called /r/MapPorn. Here the user Kepleronlyknows posted a map of the world purporting to show the longest navigable straight-line path over water without hitting land. The route began in Pakistan and followed a great circle under Africa and South America until it hit eastern Russia.

The post generated huge debate, with much head-scratching and pawing over charts and globes. The big question was whether the claim was correct—could there be a different straight-line route over water that was longer but uninterrupted by land of any kind? At the same time, same question arose for land—what was the longest straight-line route uninterrupted by lakes or seas?

For cartographers, it is clear that the answers would have to follow a great circle: an arc along one of the many largest imaginary circles that can be drawn around a sphere. Great circles always follow the shortest path between two points on a sphere. But how to find the great circles that contain the solutions?

The longest straight-line land journey on Earth.

We now have an answer thanks to the work of Rohan Chabukswar at the United Technologies Research Center in Ireland and Kushal Mukherjee at IBM Research in India. These guys have developed an algorithm for calculating the longest straight-line path on land or sea.

One way to solve this problem is by brute force—measuring the length of every possible straight-line path over land and water. This would be time-consuming to say the least. A global map with resolution of 1.85 kilometers has over 230 billion great circles. Each of these consists of 21,600 individual points, making a total of over five trillion points to consider.

The longest straight-line sea journey without hitting land.

But Chabukswar and Mukherjee have developed a quicker method using an algorithm that exploits a technique known as branch and bound.

This works by considering potential solutions as branches on a tree. Instead of evaluating all solutions, the algorithm checks one branch after another. That’s called branching, and it is essentially the same as a brute-force search. But another technique, called bounding, significantly reduces the task. Each branch contains a subset of potential solutions, one of which is the optimal solution. The trick is to find a property of the subsets that depends on how close the solutions come to the optimal one.

The bounding part of the algorithm measures this property to determine whether the subset of solutions is closer to the optimal value. If it isn’t, the algorithm ignores this branch entirely. If it is closer, this becomes the best subset of solutions, and the next branch is compared against it.

This process continues until all branches have been tested, revealing the one that contains the optimal solution. The branching algorithm then divides this branch up into smaller branches and the process repeats until it arrives at the single optimal solution.

The trick that Chabukswar and Mukherjee have perfected is to find a mathematical property of great-circle paths that bounds the optimal solution for straight-line paths. They then create an algorithm that uses this to find the longest path.

“The algorithm returned the longest path in about 10 minutes of computation for water path, and 45 minutes of computation for land path on a standard laptop,” say the researchers.

It turns out that Kepleronlyknows was entirely correct. The longest straight-line path over water begins in Sonmiani, Balochistan, Pakistan, passes between Africa and Madagascar and then between Antarctica and Tierra del Fuego in South America, and ends in the Karaginsky District, Kamchatka Krai, in Russia. It is 32,089.7 kilometers long.

“This path is visually the same one as found by kepleronlyknows, thus proving his [sic] assertion,” say Chabukswar and Mukherjee.

The longest path over land runs from near Jinjiang, Fujian, in China, weaves through Mongolia Kazakhstan and Russia, and finally reaches Europe to finish near Sagres in Portugal. In total the route passes through 15 countries over 11,241.1 kilometers.

The question now is: who will be the first to make these journeys, when, and how?

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1804.07389 : Longest Straight Line Paths on Water or Land on the Earth

Author Emerging Technology from the arXiv

Posted Oct. 2020

All about Point Nemo, discovered three decades ago.

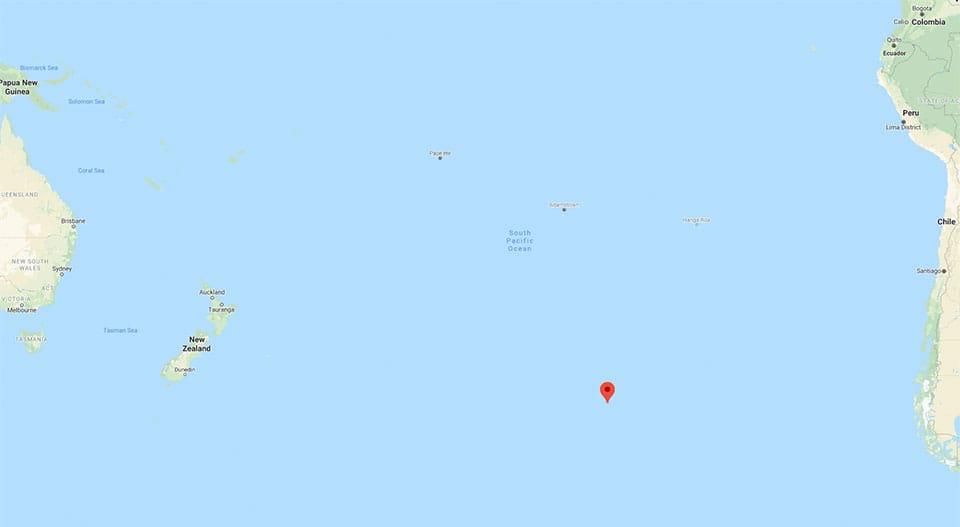

Point Nemo is the location in the ocean that is farthest from land.

You can't get farther away from land than 'Point Nemo.'

Want to get away from it all? You can't do better than a point in the Pacific Ocean popularly known as 'Point Nemo,' named after the famous submarine sailor from Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

This remote oceanic location is located at coordinates 48°52.6′S 123°23.6′W, about 2,688 kilometers from the nearest land—Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands, to the north; Motu Nui, one of the Easter Islands, to the northeast; and Maher Island, part of Antarctica, to the south.

Want to get away from it all? You can't do better than a point in the Pacific Ocean popularly known as 'Point Nemo,' named after the famous submarine sailor from Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

This remote oceanic location is located at coordinates 48°52.6′S 123°23.6′W, about 2,688 kilometers from the nearest land—Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands, to the north; Motu Nui, one of the Easter Islands, to the northeast; and Maher Island, part of Antarctica, to the south.

|

Last updated: 1/04/21

Author: NOAA |

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

8 facts about Point Nemo.

Impress your closest mates, the astronauts, with your knowledge of the world's hardest-to-reach place.

Impress your closest mates, the astronauts, with your knowledge of the world's hardest-to-reach place.

1) The Volvo Ocean Race boats are racing past an iconic point – Point Nemo, the world's most lonely place – on Leg 7, and here's everything you need to know about the place which is regarded the hardest-to-reach location on planet Earth.You can't actually see it. That's because ‘Point’ Nemo isn’t actually a bit of land. It’s an invisible spot in the vast Southern Ocean furthest from land, in any direction. (Other poles of inaccessibility include the Eurasian Pole, in China, or the Southern Pole of Inaccessibility in Antarctica – a very difficult place to visit.)

2) It's pretty far from anywhere else. 2,688km away in every direction, to be precise. Either in the Pitcairn Islands, Moto Nui in the Easter Islands, and Maher Island in Antarctica. If you’ve got to decide, we’re going to suggest heading for the Easter Islands – Ducie Island is a non-inhabited stretch of rock about 2km long, and Antarctica is, well, Antarctica.

3) It's only officially 25 years old. Point Nemo didn’t technically exist until 1992 – or if it did, we didn’t realise it. A Croatian-Canadian survey engineer Hrvoje Lukatela used a geo-spatial computer program to figure it out. SPOILER ALERT: He didn't even go there, using technology to calculate the exact location. He realised that since the earth was three-dimensional, the most remote ocean point must be equidistant from three different coast lines.

4) Point Nemo is a source of excitement for scientists. In the 90s, a mysterious noise was picked up less than 1,250 miles east of Point Nemo. The sound, dubbed "the Bloop", was louder than a blue whale – leading to speculation that it was made by some unknown sea monster – and had oceanographers all worked up. After much trepidation, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) worked out that it was the sound of a giant iceberg fracturing and cracking.

5) It isn't named after a fish. It's moniker is a tribute to Captain Nemo from Jules Verne's '20,000 Leagues Under The Sea' – and the Latin translation of ‘Nemo’ actually means ‘no man’, a fitting name for a spot so lonely. When the boats passed Point Nemo they were closer to astronauts on the space station than to other humans on Planet Earth.

6) There are rumours that it's a space junk cemetery. With no-one around, it's the perfect place to discard of old rockets and satellites. Over 100 decommission space craft are thought to lie in the area.

7) Volvo Ocean Race is leading groundbreaking scientific exploration in the area. No-one goes to Point Nemo – I mean, why would you? – but in 2017-18 the Volvo Ocean Race boats will be collecting samples as part of the Science Programme, funded by Volvo Cars. The boats are dropping drifter buoys at specific locations around Point Nemo, which will collect key metrics for scientists around the globe. Two teams – Turn the Tide on Plastic and team AkzoNobel – are gathering microplastic data to contribute to an ongoing study which aims to provide an ocean health snapshot based on samples collected along the race track.

8) You can go there, if that's your thing – just don't expect a gift shop. Just punch these digits into your GPS [45º52.6S, 123º23.6W] and start sailing – and remember, once you’re there, you’ve got just as far to go to get back to land. Don’t forget to wave hello to the guys in space!

8 facts about Point Nemo - The Ocean Race

March 25, 201808:48 UTC

Text by Jonno Turner

2) It's pretty far from anywhere else. 2,688km away in every direction, to be precise. Either in the Pitcairn Islands, Moto Nui in the Easter Islands, and Maher Island in Antarctica. If you’ve got to decide, we’re going to suggest heading for the Easter Islands – Ducie Island is a non-inhabited stretch of rock about 2km long, and Antarctica is, well, Antarctica.

3) It's only officially 25 years old. Point Nemo didn’t technically exist until 1992 – or if it did, we didn’t realise it. A Croatian-Canadian survey engineer Hrvoje Lukatela used a geo-spatial computer program to figure it out. SPOILER ALERT: He didn't even go there, using technology to calculate the exact location. He realised that since the earth was three-dimensional, the most remote ocean point must be equidistant from three different coast lines.

4) Point Nemo is a source of excitement for scientists. In the 90s, a mysterious noise was picked up less than 1,250 miles east of Point Nemo. The sound, dubbed "the Bloop", was louder than a blue whale – leading to speculation that it was made by some unknown sea monster – and had oceanographers all worked up. After much trepidation, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) worked out that it was the sound of a giant iceberg fracturing and cracking.

5) It isn't named after a fish. It's moniker is a tribute to Captain Nemo from Jules Verne's '20,000 Leagues Under The Sea' – and the Latin translation of ‘Nemo’ actually means ‘no man’, a fitting name for a spot so lonely. When the boats passed Point Nemo they were closer to astronauts on the space station than to other humans on Planet Earth.

6) There are rumours that it's a space junk cemetery. With no-one around, it's the perfect place to discard of old rockets and satellites. Over 100 decommission space craft are thought to lie in the area.

7) Volvo Ocean Race is leading groundbreaking scientific exploration in the area. No-one goes to Point Nemo – I mean, why would you? – but in 2017-18 the Volvo Ocean Race boats will be collecting samples as part of the Science Programme, funded by Volvo Cars. The boats are dropping drifter buoys at specific locations around Point Nemo, which will collect key metrics for scientists around the globe. Two teams – Turn the Tide on Plastic and team AkzoNobel – are gathering microplastic data to contribute to an ongoing study which aims to provide an ocean health snapshot based on samples collected along the race track.

8) You can go there, if that's your thing – just don't expect a gift shop. Just punch these digits into your GPS [45º52.6S, 123º23.6W] and start sailing – and remember, once you’re there, you’ve got just as far to go to get back to land. Don’t forget to wave hello to the guys in space!

8 facts about Point Nemo - The Ocean Race

March 25, 201808:48 UTC

Text by Jonno Turner

Posted June 2023